When we speak of a desert horse most people will immediately assume the conversation is about Oriental horses, or just Arabian horses. But the Desert Bred horse is generally also seen as a concept that no longer exists. But it does, in the Namib desert.

The past century feral horses have been living in this vast land surrounding the Garub water hole, which has allowed them to survive. Although the Namib is called a desert, the areas in which the feral horses are found vary in topology, geology and climate. Plains of sand and dry rivers aren’t the only features of the roughly 2000 km long Namib. There are also low mountains and desert gravel, which provide the horses but also their grazing competitors the gemsboks and springboks, their main diet. When we think of desert climate we imagine a searing heat but the average temperature in the Namib throughout the year is 18°C, making it a ‘cool desert’.

Due to the scarcity of water, grazing competition and predators such as the spotted hyena and the jackal, the feral horse population of the Namib has always remained small. The total number never exceeding 280 horses. Studies have shown their ability to adapt to harsh environments to stem from their behavior rather than genetic extraordinary resilience. Patterns were discovered in their ratio of feeding, travel and resting as well as temperature.

The genetic makeup of the Namib desert horses is however very interesting as there are many theories about their origin. Since horses are not native to the south of Africa it still somewhat a mystery where these horses have come from. Among the theories about the origin of the feral horses is the idea that the Dutch and English colonists from the Cape moved upwards to what is now Namibia and took their (war)horses with them. Another possibility was that the indigenous peoples such as the Khoikhoi, who are known to have stolen some of the immigrant horses and started keeping them, were responsible for the arrival of horses to the Namib.

Because the Namib desert horse resembles the TB and other European breeds, a theory about how a ship carrying English TB’s stranded on her way to the Cape surfaced. Although a romantic idea , it is unlikely that horses would first swim to shore in large numbers and then traveled approx 318 km to reach the Garub water hole. Another, more detailed, theory is that of the horses escaping from Duwisib Castle, about 200 km from Garub. German Baron Hans-Heinrich von Wolf bred horses there from 1908 until WWI broke out in 1914. Although this story gives us a bit of an idea towards the time we think the first (feral?) horses may have appeared in the Namib, the distance to the water hole still remains an issue.

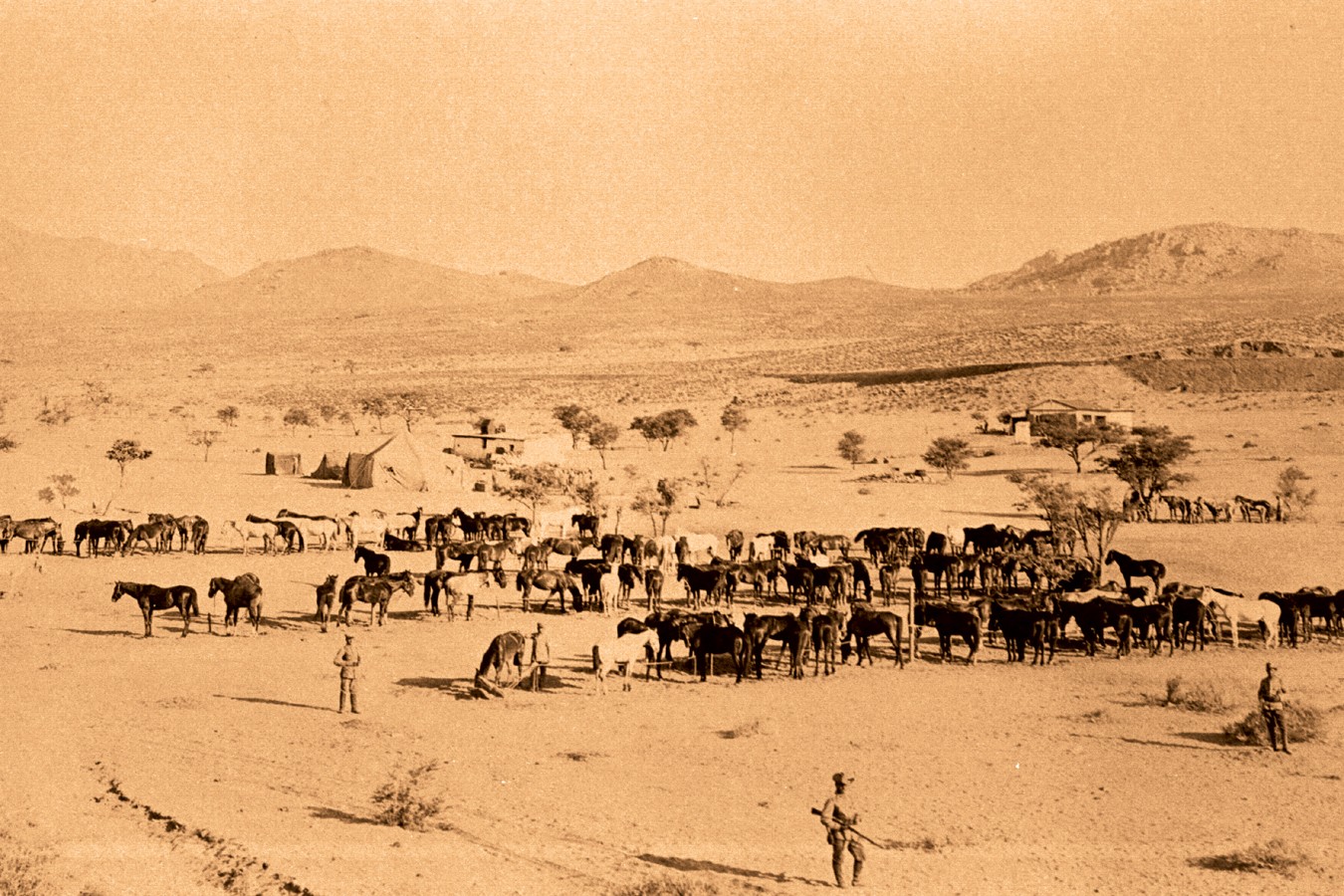

The first more serious reports of larger number of horses in the area do stem from the same time period. Union of South Africa troops were stationed near Garub during the war with reportedly up to 6000 horses. A German military report from 1915 describes the bombing of the encampment and 1700 grazing military horses. It is thought that in the heat of the moment the Union forces did not manage to retrieve all of the horses as they quickly marched on the Germans, and the horses left behind considered the foundation stock of the feral Namib desert horse. Although this theory is very attractive because there is no large distance for ‘lost’ or ‘escaped’ horses to travel, it seems that it is unknown whether or not the ‘forgotten’ horses were retrieved by anyone or remained lost.

Kreplin among his stud animals on the farm Kubub near Aus. (photo: private collection Mannfred Goldbeck)

The most plausible theory towards the origin of these feral horses is the stud farm of Mr. Emil Kreplin (gestüt Kubub) in Lüderitz. Kreplin was the mayor of Lüderitz and responsible of building the new train tracks up-country following the diamond rush in 1908. He bred horses for both the work in the mines and the railways as well as for the luxurious races as his town grew larger between 1909-1914. The Kubub studfarm was located close to the Sperrgebiet, a marked out area which the colonial government tried to protect by giving mining rights to just one company (Deutsche Diamantengesellschaft) and thereby rendering the Sperrgebiet forbidden terrain for all others. When the German forces fell and South African forces took over the Sperrgebiet remained intact under new ownership (De Beers).

Being one of the founders of the Deutsche Diamantengesellschaft, Kreplin used his diamond wealth to import horses for his stud. During the war he fell in Union hands but returned to his post as mayor of Lüderitz after the war, however he eventually left Namibia in 1920. His horses now left ownerless and fenceless are assumed to have wandered into the Sperrgebiet where they would be safe from hunters and other human dangers.

A study of the genetical makeup of the Namib desert horse showed extraordinary results. Only Blue Star Arabians have a lower genetic variation than the desert horses, meaning they descend from a very small number of foundation horses. Surprisingly, the Namib horses fit within the ‘Oriental’ cluster, having a lot in common with the Arabian, Turkoman, Akhal Teke, Kurd, Khuzestan Arabian, and most interestingly, the Shagya (Hungarian) Arabian. A bit further away they have a connection to Iberian breeds, TB and North American gaited breeds. Most of the breeds listed here can be explained by the fact that there would have been Union horses among the foundation of the Namib desert horses. South African forces would have had both TB and local horses, that were the result of earlier colonial efforts of creating the perfect warhorse. Indonesian horses, carrying both Spanish and Arab/Persian blood were brought to South Africa by the Dutch settlers. British immigrants later added the TB and Indian blood. The only odd name on the list seems to be the Shagya Arabian. Who brought that influence to Africa? It may have been Kreplin as the Hungarian horses were popular warhorses at the time, but I have not been able to find records yet.

A couple of photos raise a few more questions. For example the fact that there are clearly some grey horses in the German herds and the various studies and sources about the Namib Desert horse state that there are no greys among the current population. It almost seems as if grey is not a ‘natural’ color, which leaves question marks at the idea of the grey DesertBred Arabian for example.

Horses of the German colonial forces near the city Aus. Source: National Archive of Namibia

The size of the horses of the German forces in some of the photos also seems a bit odd. Most sources state that they rode imported horses and also bred their own, suggesting they were not interested in using locally available horses, if there were any. However in the photo below it is clear that these horses are smaller than the suggested Trakheners of the German cavalry… Another photo shows an officer on a rather large horse, probably imported as it looks similar to the ones featured in images from Europe during WWI.

For now the ‘origin’ of the Namib desert horses will remain an unanswered question, however there is a very important lesson to be learned from their existence. They may perhaps represent the only ‘breed’ not created by man. The extremely low genetic variation suggests that they are now ‘purebreds’ in their own right. As such, the SA Boerperd registry has accepted the crossbreeding of Namibs in their studbook following an experiment that isolated some of the Namibs in order to see if they could add beneficial qualities to domestic stock. Because it is still assumed that any Desert horse has to possess certain qualities to be able to survive in the extremely hostile environment. Much of the talk surrounding the Oriental horses has claimed their appearance, and especially that of the Arabian, is a direct result of the breed being ‘shaped’ by the desert. Yet the Namibs have survived without the help of humans and do not resemble the Oriental horses they are so genetically close to, leaving a serious question mark in relation to a ‘unified shape’ of the concept of the Desert horse.

Very interesting piece. In terms of grey as a natural colour, the greying gene acts on coat colour no matter what colour genes are present. Since it’s expressed even in heterozygous greys it is easy to select out, so it’s possible that natural selection has done its job there!

It’s the same genetics that make us go grey-haired as well. Maybe also selective pressures because grey-skinned horses are more susceptible to melanomas.

Grey skinned or pink skinned?

Or….grey hair on a pink skin or grey hair on a black skin?